This article was originally published by Metropolis Magazine as "The Build Up."

This November, the Manetti Shrem Museum on the University of California, Davis, campus opened to the public. Designed by New York City–based SO-IL with the San Francisco office of Bohlin Cywinski Jackson, the museum pays homage to the agricultural landscape of California’s Central Valley with an oversize roof canopy. The steel members of the 50,000-square-foot (4,650-square-meter) shade structure, nearly twice the size of the museum itself, reference the patterning of plowed fields and create a welcoming outdoor space for visitors. It is both expressive and practical, but getting that balance wasn’t easy.

SO-IL, founded by Florian Idenburg and Jing Liu in 2008, has a portfolio filled with smaller projects, installations, and exhibition-related work. The Manetti Shrem Museum is easily the firm’s largest work to date, demanding a rigorous design-build process while maintaining a strong conceptual vision. In short, it required architecture.

For some emerging firms, architecture’s delicate pas de deux between ideas and physical realization is a newfound pleasure and challenge. The economic consequences of the late-2000s recession meant that many young designers entered into practice at a time of limited building opportunity. Research dominated, and commissions—seemingly juicy ones—came in the form of installations or exhibitions. Although a great way to develop conceptual ideas on architecture, these smaller, temporary works sometimes prove an awkward training ground for larger-scale, permanent projects.

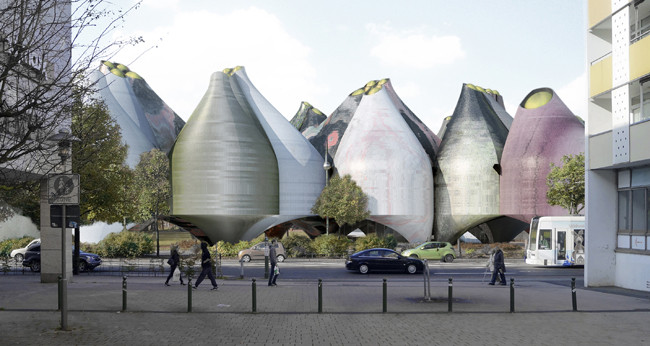

Michael Young of New York City-based Young & Ayata experienced this firsthand last year, when the firm was named one of two first-prize winners in the international competition for the new Bauhaus Museum in Dessau, Germany. His practice explores lofty questions of objecthood, nature, and representation through research and image making. Yet for the last stage of the competition, Young and his collaborator, Kutan Ayata, were asked to produce detailed construction documents and a budget to accompany the arresting scheme—multicolored clusters of organically shaped “vessels” in a park setting. Although the commission ultimately went to a more conservative project from Spanish architects González Hinz Zabala, Young noted in remarks during SCI-Arc’s 2015 Right Now symposium that evolving an experimental design into something ready for construction was a stranger process than the speculative or analytical work they were more accustomed to. “At the time, we were knee-deep in figuring out how to build,” he says on recent reflection. “We came up with a convincing piece of construction, convincing in all rights, but over budget.” The structure of the competition didn’t allow for readjusting the scheme to fit the price tag, so the architects were left frustrated by their own trial in complexity.

“Money” can be a dirty word in design circles—especially in the academy, where any whiff of budget, value engineering, or even the dreaded “professional practice” makes defenders of the discipline recoil in disgust. Budget is lowbrow, concept highbrow. But steering the budget toward a design imperative can make or break a project. Today, Young & Ayata has a more deliberate relationship with the building process. For an upcoming apartment building in Mexico City, the architects have constrained their formal language to the facade. “All the design effort was put into a couple experimental moves that we thought we could pull off,” Young says of a project that privileges realization of an actual edifice.

“You have to know where the key moments are in a project where you either keep the concept or lose it,” says Idenburg. SO-IL won the Manetti Shrem Museum commission in a 2013 competition and was required to stay within a $30 million budget. To ensure that their concept carried through to realization, the architects labored over the canopy design, tweaking it in collaboration with Bohlin Cywinski Jackson and facade consultants Front Inc. Intensive modeling helped them create a cost-efficient design, and together they developed a Grasshopper script to control the length of steel members and every connection. The end effect, adds Idenburg, was that each piece was tied to an exact cost. “We were able to play with the model and the spacing of the steel while always guaranteeing the final price.”

A year after winning the Turner Prize for art, and thus scrambling the art world’s preconceived notions of architectural practice, Assemble Studio opened its own construction company. The London collective was founded in 2010, and while its socially minded designs span furniture to installation to building, the 18-member group is dedicated to a practice—however theoretical to start—that’s grounded in the real world. Taking over the reins of production would ostensibly allow them to explore territory between design and delivery—and, as with some of their work to date, offer transparency in a process that’s generally pretty opaque to a larger public.

“We are interested in playing with existing material and industry processes,” explains Assemble member Maria Lisogorskaya. “We enjoy the unexpected changes and adaptations which can be a result of working with engineers, fabricators, and other building experts—these make our work richer.” Completed projects have yet to manifest, but there’s something exciting and thought-provoking in situating architectural experimentation at the heart of construction.

Perhaps, then, a practice’s maturity can be judged in the ways it hardwires concept into the construction practice. When the Mexico City-based firm Productora designed a textile museum and community center in the Mexican town of Teotitlán del Valle, Oaxaca, architect Wonne Ickx knew that some details would succumb to budget cuts. The work-around was to design everything in concrete—“even the sinks,” says Ickx—and then have the structural engineer sign off on the drawings. The designers had anticipated changes during the building process and gambled that the client wouldn’t tamper with the engineering package. It paid off. The museum is scheduled to open in March 2017, with a full complement of concrete details.

“We always have a very strong concept or radicality in how we try to do architecture,” says Ickx. Still, he stresses the importance of a kind of radicalism in practicality and the building process. It’s something that he sees as part of the Mexican architectural tradition, where the basic agenda for architecture is far closer to a buildable project.

“There’s an understanding that the set of buildings realized by the architect are the work of the architect, not the postures or the critical writing,” he says.

Ickx, who also teaches in the architecture department at UCLA, is critical of what he sees as a primarily U.S. phenomenon—an enormous stigma on building and detailing. He sees it in his students, who worry more about the overall integrity of a formal agenda than the complex and highly negotiated process it takes to get something built. “In the end you have to make a concession,” says Ickx of the act of going from concept to construction. “That’s where the architectural project is—one way or another. How you make it determines if it’s a good or bad building.”